Long-Term Assets in a Real-Time World

Pitting and corrosion in steam turbine blades are accelerated by cycling operation.

Pitting and corrosion in steam turbine blades are accelerated by cycling operation.Rapid changes in electric power markets are posing new challenges for operators of generating facilities across the country. While spark spreads are narrowing, green energy mandates are driving expansion of variable generation. Shale gas reserves have pushed fuel and electricity prices to historic lows, just as new environmental rules are putting pressure on fossil-fired plants. Baseload facilities, designed to operate virtually 24/7, are cycling to accommodate market fluctuations.

Against this backdrop, we spoke recently with Tom Alley, vice president of generation at the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), about how the organization is helping its members evaluate their fleets and establish long-term strategies for each asset class. In the first of this two-part series, we focus on operations and maintenance (O&M) costs.

FORTNIGHTLY Operations and maintenance (O&M) costs play a major role in deciding whether to upgrade or retire a generating asset. What studies are you currently working on to help your members make that call?

ALLEY O&M costs are obviously fundamental to utility resource planning, so it’s a key component in a lot of the research we’re doing.

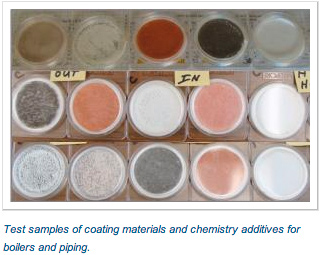

We have lab studies underway that look at ways to extend the life of components in both coal and combustion turbine units. Several, for example, will quantify the impact of applying different coating materials to various power plant components.

In one, we’re testing thermal barrier coatings on gas turbine hardware to provide better high-temperature protection for air-cooled combustor components. We want to see, for example, how coatings on turbine blades will extend the blade life and reduce the overall maintenance costs.

In another, we want to determine the effectiveness of using new coatings to reduce boiler tube erosion and corrosion. These tests will assess a variety of weld overlays, thermal sprays and ceramic coatings, and also examine the impacts of fuels and fuel blends for a given temperature and coating.

Extending the life of key components will reduce the cost of operating a specific unit and may, in some cases, make it a more economically viable member of the fleet.

FORTNIGHTLY How do new, digital technologies fit in?

ALLEY Monitoring and diagnostics technologies are coming down in cost, so we’re looking to deploy sensors throughout the plant to perform real-time component monitoring and deliver that information to a centralized diagnostic center. That will allow a utility’s O&M staff to review real-time operating parameters and make informed decisions about the plant’s status.

A good example of this is turbine blade vibration sensors. EPRI is leading efforts to create a microelectromechanical (MEM) sensing system for direct, online vibration monitoring of large blades in low-pressure steam turbine stages to detect damage and avoid catastrophic failures. The system is also expected to be applicable for combustion turbine compressor blades. The system will employ a wireless electronic device called a mote, with a footprint of just over 1 square inch, that’s small enough to be mounted at the blade tip. EPRI is working on a prototype that is scheduled for evaluation in 2014.

The idea is that if a utility can collect and remotely monitor real-time operating data, it can schedule repairs for cause, rather than scheduled maintenance. For example, a person might replace the oil in their car every 3,000 miles. That’s a maintenance practice. If they had a sensor in the engine that could track the oil chemistry and at 3,000 miles it tells them the chemistry looks okay, there aren’t a lot of particulates in it, why would they change the oil? Why not wait until the sensor says it’s time?

That obviously doesn’t apply to a power plant, but it’s an example of repairing for cause, versus repairing for maintenance practice. By gathering operating data on a day-to-day basis an O&M manager could say, “Okay, now we have an issue, we need to make this part of the next outage,” rather than saying, “Oh, it’s that time of the year again and our maintenance schedule says we have to replace component X.”

FORTNIGHTLY So, like the boiler tube and turbine blade coatings, this is another way to extend the life of certain components and reduce O&M costs?

ALLEY Right, plus it could also help the industry address its workforce issue. An awful lot of expertise in this industry is entering or nearing retirement. And many of the experienced peop

le still in place are overseeing major projects, like plant modifications or even new construction.

Being able to capture real-time operating data and have it in a centralized location can serve multiple purposes. First, the more experienced senior people can monitor data from the whole fleet, as opposed to a single unit or plant. And newer people, the next generation if you will, can use it as a learning experience and gain important insight to plant and fleet O&M.

So if you view the loss of expertise from an operational standpoint, this is another way technology can be used to reduce O&M costs.

FORTNIGHTLY In a 2012 editorial you said that while it’s currently cheaper to generate electricity by firing natural gas, basing fleet decisions just on fuel price alone overlooks some key inputs. What are some of these inputs?

ALLEY Well, the natural gas market is a whole discussion in and of itself, but from a power industry perspective we’re all concerned about the implications of having a single fuel source. And right now, natural gas appears to be the destination fuel.

But for many utilities the crossover point between burning natural gas and burning coal is somewhere in the $2.50 to $4 range. Of course, it depends on the coal you burn, the cost of the coal, and the transportation cost. But generally speaking, as the price of natural gas moves between $3- and $4-mmBtu—which is what we’ve seen a lot of in 2013—most of our members are switching fuels. Many are burning gas one week and coal the next, so right now everything depends on natural gas pricing.

The point is that when you transition from one fuel to the other and then back again—shutting certain units down and laying them up for a week or two, then starting them up again—there’s substantially more wear and tear on the components.

Flexing units, especially to this extent, obviously increases your maintenance costs. You have substantially more wear and tear and the unit’s efficiency can and probably will decline. So there are a number of variables that come into play when you start fuel switching.

And this will likely continue. In the U.S. this year we’re probably going to see more coal burned than natural gas. Last year it was about even because gas prices were often sub-$3. This year natural gas has been in the $3 to $3.50 range. Most of the indicators I’ve seen say we should burn more coal this year. It’s not going to be dramatic, but there will be an uptick in coal.

FORTNIGHTLY – In the same editorial you mentioned “hidden consequences” for the industry down the road. Can you expand on that?

ALLEY The boom in gas has been labeled as a bust for coal. But the truth is, it has implications for all generation assets, including combined-cycle plants. The challenge for the industry is to understand and adapt.

In the editorial, I noted that older coal plants in the U.S. are most often used for balancing intermittent loads. But many of those plants are being retired due to a combination of age and anticipated requirements for expensive new emissions controls.

That means the remaining baseload units, including a growing number of combined-cycle and even nuclear units, face operating flexibility challenges.

When I speak of hidden consequences, I mean this flexing of the units and the wear and tear that type of operation causes. In most cases, it takes years before equipment damage becomes apparent, so if you’re an electric utility putting a specific unit (or units) through the paces this year and damage occurs, you may not even realize what you’ve done for several years out.

So, again, that’s what our studies are targeting—ways to help our members monitor and understand the long-term implication of operating assets in today’s environment. That’s the Holy Grail right now. When you’re evaluating the fleet, you need to know the consequences of certain operational strategies now, not several years down the road. And that’s what we’re looking at.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR Scott M. Gawlicki is Fortnightly’s contributing editor, based in West Hartford, Ct.

ABOUT THE SOURCE Tom Alley is responsible for EPRI’s R&D team, which is focused on research, development, and the application of fossil technologies for both existing and future generating assets. He has 29 years of experience in the energy industry, and his experience includes fossil and nuclear power. He joined EPRI in 2007 as senior program manager for major component reliability R&D, and most recently served as director of advanced generation research, which includes renewable generation, carbon capture and storage, generation planning, and industry technology demonstrations. Before joining EPRI, Alley worked at Duke Energy, leading a centralized corporate team of metallurgists, engineers, and technical personnel responsible for the evaluation, inspection, and repair of nuclear power plant components.